As all Tolomato fans know, the cemetery was originally a “refugee Indian mission.” After the British Colonial Governor James Moore of South Carolina wiped out the Florida mission chain in attacks over a several year period, mostly notably 1704 and 1706, the few surviving Indians were brought into St Augustine and settled in five different villages, which were served by the Franciscans from what is now the St Francis Barracks. We know the locations of three of them: La Leche, La Punta and Tolomato, but there are two others in what is now Lincolnville whose exact location is unknown.

The villages were small, and Tolomato was probably the largest but nonetheless had fewer than 100 people or so in its heyday. They were mostly Guale Indians who had actually first been moved over a century earlier, during an Indian rebellion on the Georgia coast near their original home, and had spent almost 100 years living on a river that was known, of course, as the Tolomato River, which runs past today’s Guana River Preserve.

They were attacked by Moore, and in 1706, the Spanish governor issued an order calling the Indians into St Augustine and they fled to the city. Tolomato was located just at one of the west-facing city gates, near the redoubt where the cannons were, and was a safe location…although at least one of the Tolomato Indians was killed in the 1740s, defending the city against another wave of British-allied Indian attackers.

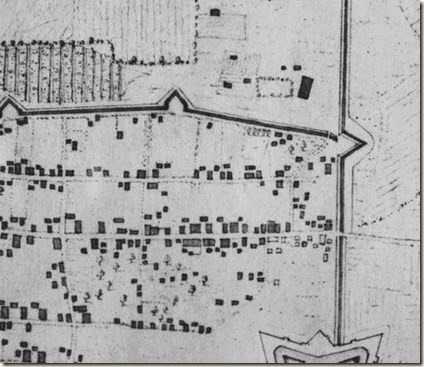

Above are two maps of St Augustine, the first by the Spanish engineer Juan Elixio de la Puente in 1764, and the other by the British engineer Moncrief in 1765. Tolomato would be at the upper right, outside the city walls and near the Cubo Line that went along today’s Orange Street.

We have virtually no other visual or archaeological records of the missions, except for a 1726 mention of a wooden chapel with a four-story stone bell tower at Tolomato. When the British arrived in 1763, the Spanish citizens, including the Indians, went to Cuba and abandoned their properties. The British took over and used the chapel for firewood, but they left the bell tower, and in describing his journey through Florida in the 1760s, the naturalist Bartram mentions the tall but narrow (about 20’ on each side) bell tower.

It stood until somewhere between 1793 and 1800, when it was taken apart so that the stones could be used in building the current Cathedral. One of the blocks of stone fell on the vault or grave of Fr. Pedro Camps, the Minorcan priest, and crushed it, leading to his reburial at the Cathedral in 1800.

But we have one question: Where exactly was the Franciscan chapel?

It was not located where the current Varela Chapel is located, because that piece of land was bought in 1853 specifically for building the chapel. And looking at the maps, it seems that the chapel was not even in the center of the Indian village. The de la Puente maps of the 1760s show it as a little northeast of the center of the modern cemetery, and one map shows it with another structure joined to it like an ell – this may have been the belltower joined to the chapel.

So the long and the short of the story is that we’re looking for any trace of the bell tower. But …GPR to the rescue!

Then last week, FPAN’s Kevin Gidusko, shown above, came out with his GPR equipment – and we think we’re getting close. If you want to know more about it, come out and visit us this Saturday, March 21, and ask us where we think it was.

And if you’re interested in the Indian population, go to the Flagler College conference on the Yamasee Indians to be held on April 17-18th. You can sign up here: http://yamaseeconference.weebly.com/. Meanwhile, look at those little red flags…and wonder.