The name is that of a very old and historic family, originally the Vela Ximénez family, descendants of the Dukes of Aquitania, who came in the 9th century to the area now known as Navarra, now a part of Spain, but at that time under the control of the French Dukes of Aquitaine (as a point of reference, this is the region that includes modern Toulouse). The family became the Dukes of Álava, a region currently the subject of dispute between Navarra and País Vasco. Incidentally, most of the royal houses of Europe are related to the Dukes of Aquitaine.

After being involved in the usual power struggles that were a daily feature of life in the warring kingdoms making up Spain, several family members sided with the rulers of León (see above map of 13th century Spain) in their fight against the neighboring kingdom of Castilla. But they had to flee after one family member murdered – in the Cathedral - the heir to the throne of Castilla. They took off for the remote mountains of the areas now known as Asturias and Cantabria. They settled in the town of Mier, located in a remote mountain valley in the jagged mountains now called the Picos de Europa, next to the River Cares.

.

The name of the town probably comes from the Latin or Romance word messis (mies in modern Spanish), which meant harvest or crop, usually of grain. The tiny town itself in in a narrow part of the valley, but is located in the area of the common lands where the inhabitants of the valley cultivated their big crops, such as grain. Nowadays it devotes itself to cheesemaking, and cheeses from Peñamellera Alta, the name of the region, have their own denomination of origin.

Taking the name of the town as their own, the de Mier (“from/of Mier”) family became one of the most important families in Spain and Latin America and one that is still influential today. The ancestral homes of the de Mier family can still be visited in Mier, as well as parts of Cantabria to which some members relocated. There are several branches of the family, but certain things, such as the fleur de lis, are common to their various coats of arms. The fleur de lis indicates the Aquitanian origin of the original family.

In the 13th century, the Ximenez family, soon to become “de Mier,” were given the privilege of having the Cross of St Andrew as part of their coat of arms. It symbolized their participation in the decisive Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in 1212, fought on St Andrew’s Day. This was a significant victory in the fight to expel the Muslim invaders from Spain, a fight which actually began not far from Mier, in those same mountains in the year 722, about 10 years after the invasion. The Asturians were the first to successfully resist the invaders and the fight continued for centuries, moving from the north to the south until the decisive defeat of the Arabs in Granada by the troops of Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492. The Cross of St Andrew is also the “X-like” cross that appeared on the Spanish battle flag that flew over Spanish St Augustine.

But over the generations, different elements were added or dropped. Below is a de Mier coat of arms that appears on many buildings in Mier. Their motto can be roughly translated as: “Forward, man of Mier, because you are the bravest.”

Because they were hidalgos (nobles) registered in the Asturian records of “hidalguía” (nobility) based on their ancestry, de Mier family members were important in their region and were traditionally involved in politics and the judiciary. Many members of the de Mier family in Spain are still involved in scholarship, law or politics, both in Asturias and in other parts of Spain to which this large and ancient family scattered. And of course, they are still marrying into other families: the grandmother of Rainier III of Monaco is a de Mier.

The four main branches of the family in Latin America are the de Mier-Teran, de Mier-Noriega (in Mexico), de Mier y de la Torre (Colombia) and de Mier y Arce (Peru). Fernandez de Mier is thought to be one of the oldest forms of the name. Part of this family went to Andalusia in the 18th century and settled in Cádiz, where they became successful merchants. From the 19th century onwards, they built a trade empire on dealings with the Spanish Caribbean (of which St Augustine was a part). Antonio Jose Fernandez de Mier came from this family, since the inscription records that he was born in Cádiz, like his father.

We’ll devote another post to more information about Antonio Jose Fernandez de Mier and his connections with the Micklers (a family that emigrated to South Carolina from Alsace, France in the 18th century, and then on to St Augustine in the late 18th century) and with several Minorcan families, such as the Andreu family.

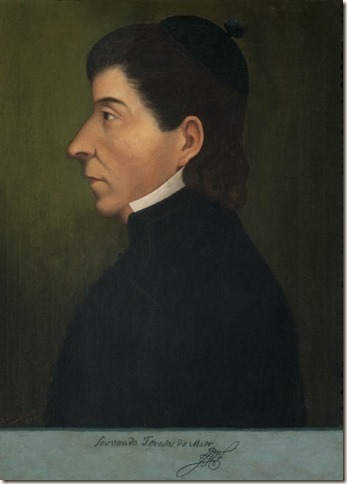

But for now a bit about Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, who started my search.

The rather firm looking gentleman in the photo was a Dominican friar, born in Monterrey, Mexico in 1765. His family lived in an area known as Nuevo León, in the northern part of the country which at one point could have been part of Texas, where there is even a town named Mier.

Fray Servando de Mier led a colorful life that started with his being exiled from Mexico to Spain because of his theory on Our Lady of Guadalupe, specifically, that the image did not appear in the 16th century but had been done in the 1st century when Saint Thomas, on his way to India, visited the Latin American continent and evangelized the Indians. It is certainly likely that St Thomas did get to India, but completely impossible that he would have made it to Latin America. But don’t forget that Columbus thought he was looking for and had arrived in India, probably leading to this theory.

Fray Servando de Mier had been exiled to Cantabria, the family’s ancestral home, but this was just the beginning for him. He got into political trouble virtually everywhere he went, since he was an early defender of the idea of independence for Spain’s Latin American colonies, particularly Mexico. During his exile, he was imprisoned for his political opinions, went to Cádiz, which was a hive of revolutionary activity, was seized by the French and spent time in Paris, somehow ended up in Rome, went back to Spain and back to various forms of imprisonment, and finally fled to London. While he was there he met a fellow Spaniard who was very involved in Latin American independence movements and they returned together to Mexico in 1822, during its War of Independence. Imprisoned again, but briefly, he finally had the pleasure of being part of Mexico’s constituent congress for the writing of the Mexican Constitution. He died in 1827 and was buried in Mexico with great honors.

However, it doesn’t end there: by 1861, he seems to have been more or less forgotten, because his remains were exhumed, along with other burials at the same location, and were sold to an Italian who exhibited them as “victims of the Inquisition.” (They weren’t.) Finally these remains ended up in Belgium, and now nothing is known of their whereabouts. So Fray Servando de Mier was as dramatic (and perhaps as much of a traveler) in death as in life.