But the old headstones remained - in English, French, Italian, German and Latin, to enumerate those that I saw – and gave me an interesting glimpse into early Charleston life. The majority of the gravestones were those of Irish or French inhabitants, the two main Catholic groups in early Charleston, but there were several that showed birthplaces in different parts of Italy, one from Switzerland, some from Austria, and one man from Transylvania, a state that doesn't even exist anymore. (Back in the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was located in a part of what is now Romania.) There were place names of all kinds, names of distant places that have been swallowed up by time, by wars, or simply by changing tastes.

But the old headstones remained - in English, French, Italian, German and Latin, to enumerate those that I saw – and gave me an interesting glimpse into early Charleston life. The majority of the gravestones were those of Irish or French inhabitants, the two main Catholic groups in early Charleston, but there were several that showed birthplaces in different parts of Italy, one from Switzerland, some from Austria, and one man from Transylvania, a state that doesn't even exist anymore. (Back in the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, it was located in a part of what is now Romania.) There were place names of all kinds, names of distant places that have been swallowed up by time, by wars, or simply by changing tastes.  The Transylvanian traveler’s stone was in Latin, and told a rather long story: His name was Matheus Leopoldus Stupich (aka Mattias Leopold Stupicz), and he was a medical doctor and botanist. It tells you that he was a Roman Catholic from Transylvania, although he is described by some historians as German and by others as Hungarian. The stone informs you in large letters that he had been sent to America by the IMPERATOR JOSEPHO SECUNDUM, referring to the Emperor Joseph II of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And indeed it was Joseph II who sent Stupich, along with four other men who were gardeners, artists or botanists, "IN AMERICUM" in 1783 to collect plant samples with the mission of finding new, hardy American plants to replace plants from the Imperial Gardens that had been killed by a severe freeze that winter. The five men set out together but before long, the artist, Bernhard Albrecht Moll, split off from the group and ended up in Charleston.

The Transylvanian traveler’s stone was in Latin, and told a rather long story: His name was Matheus Leopoldus Stupich (aka Mattias Leopold Stupicz), and he was a medical doctor and botanist. It tells you that he was a Roman Catholic from Transylvania, although he is described by some historians as German and by others as Hungarian. The stone informs you in large letters that he had been sent to America by the IMPERATOR JOSEPHO SECUNDUM, referring to the Emperor Joseph II of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. And indeed it was Joseph II who sent Stupich, along with four other men who were gardeners, artists or botanists, "IN AMERICUM" in 1783 to collect plant samples with the mission of finding new, hardy American plants to replace plants from the Imperial Gardens that had been killed by a severe freeze that winter. The five men set out together but before long, the artist, Bernhard Albrecht Moll, split off from the group and ended up in Charleston.  Moll, who was from a noble family and readily accepted by snobbish Charlestonians, supported himself by teaching art and doing the cut-out paper silhouettes popular in the late 18th-early 19th centuries, and was soon joined by Stupich and one of the gardeners, Franz Boos. Their story is told on the Clemson University website, where Stupich was named the "South Carolina German American of the Month." Above is Moll’s silhouette of Boos, which also appears on the website. They collected plant and animal specimens in the Charleston area and shipped them back to Austria, and also kept travel journals and wrote an interesting account of the Goose Creek area near Charleston. Stupich also decided to remain in Charleston and resume his work as a doctor; he lived and prospered the rest of his life there, much to the annoyance of the Emperor. He died there at the age of 62 and his stone is one of the oldest in St Mary's Cemetery.

Moll, who was from a noble family and readily accepted by snobbish Charlestonians, supported himself by teaching art and doing the cut-out paper silhouettes popular in the late 18th-early 19th centuries, and was soon joined by Stupich and one of the gardeners, Franz Boos. Their story is told on the Clemson University website, where Stupich was named the "South Carolina German American of the Month." Above is Moll’s silhouette of Boos, which also appears on the website. They collected plant and animal specimens in the Charleston area and shipped them back to Austria, and also kept travel journals and wrote an interesting account of the Goose Creek area near Charleston. Stupich also decided to remain in Charleston and resume his work as a doctor; he lived and prospered the rest of his life there, much to the annoyance of the Emperor. He died there at the age of 62 and his stone is one of the oldest in St Mary's Cemetery.  And then of course there are the graves of children and the graves of people who died "of a fever," since Charleston was subject to frequent outbreaks of mosquito borne yellow fever, just like St Augustine. There were also the graves of clergy ordained in a variety of European countries and the early US. Of course, many clergy are buried under the floor of the church itself, and the lovely painting in the dome was donated in memory of one of them, the Rev. Dr. Corcoran, by his students at the seminary in Philadelphia.

And then of course there are the graves of children and the graves of people who died "of a fever," since Charleston was subject to frequent outbreaks of mosquito borne yellow fever, just like St Augustine. There were also the graves of clergy ordained in a variety of European countries and the early US. Of course, many clergy are buried under the floor of the church itself, and the lovely painting in the dome was donated in memory of one of them, the Rev. Dr. Corcoran, by his students at the seminary in Philadelphia.  When I looked at these stones, I thought that people of our generation will never be known this way. Since modern people are either cremated and scattered or buried under small neutral "name and date only" plaques in giant lawns designed to be easily trimmed by riding mowers, we'll never know where they were born or anything about the circumstances of their lives, such as that of the young man who lies under the stone below: born in Tarbes, France to die in Charleston in 1819 as a victim of the “prevailing fever,” he was “sincerely lamented by all who knew him.”

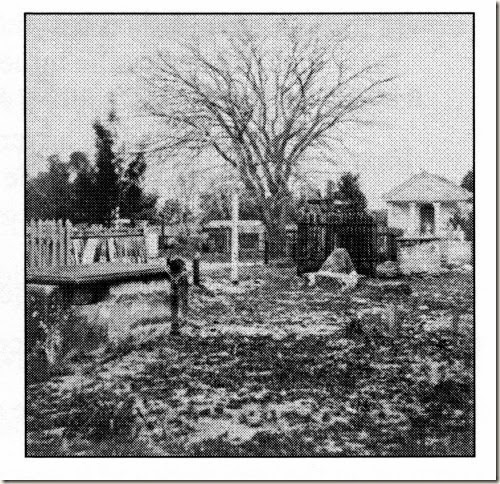

When I looked at these stones, I thought that people of our generation will never be known this way. Since modern people are either cremated and scattered or buried under small neutral "name and date only" plaques in giant lawns designed to be easily trimmed by riding mowers, we'll never know where they were born or anything about the circumstances of their lives, such as that of the young man who lies under the stone below: born in Tarbes, France to die in Charleston in 1819 as a victim of the “prevailing fever,” he was “sincerely lamented by all who knew him.”  This to me is a real loss. Perhaps we don't need to have the giant self-aggrandizing 19th century monument gone mad, but it is sad to slip into anonymity and uniformity, wiping out these unique little footpaths of history that we see here in a historic cemetery such as old St Mary's or Tolomato. The custom of detailed, individualized grave markers has come and gone throughout history. At Tolomato, for example, we have fewer gravestones than many cemeteries of the same size because the early custom was simply to put a small wooden or metal cross above the grave. Spanish grave markers for the average person at that time tended to be simple, at least in part because burials were often somewhat temporary and remains would be removed to an ossuary or another place after a certain time. In addition, until the mid-19th century, the economic situation of St Augustine was a little more fragile than that of Charleston (see the mid-late 19th century photo below). Yet we see throughout human history the desire to commemorate the deceased and preserve a few facts about his or her life so that passing strangers years later may see them and think about that life.

This to me is a real loss. Perhaps we don't need to have the giant self-aggrandizing 19th century monument gone mad, but it is sad to slip into anonymity and uniformity, wiping out these unique little footpaths of history that we see here in a historic cemetery such as old St Mary's or Tolomato. The custom of detailed, individualized grave markers has come and gone throughout history. At Tolomato, for example, we have fewer gravestones than many cemeteries of the same size because the early custom was simply to put a small wooden or metal cross above the grave. Spanish grave markers for the average person at that time tended to be simple, at least in part because burials were often somewhat temporary and remains would be removed to an ossuary or another place after a certain time. In addition, until the mid-19th century, the economic situation of St Augustine was a little more fragile than that of Charleston (see the mid-late 19th century photo below). Yet we see throughout human history the desire to commemorate the deceased and preserve a few facts about his or her life so that passing strangers years later may see them and think about that life.  An examination of the gravestones at Tolomato will also tell us these stories. Think of the story of our earliest marked burial, that of Elizabeth Forrester who died at the age of 16 in 1798, or of the sad Benet-Baya monument, commemorating the loss of an entire family. Or the happier stone of Fr. Miguel O’Reilly (d. 1812), which tells of his Irish birth, Spanish education, and New World labors.

An examination of the gravestones at Tolomato will also tell us these stories. Think of the story of our earliest marked burial, that of Elizabeth Forrester who died at the age of 16 in 1798, or of the sad Benet-Baya monument, commemorating the loss of an entire family. Or the happier stone of Fr. Miguel O’Reilly (d. 1812), which tells of his Irish birth, Spanish education, and New World labors.

Perhaps gravestones will someday come back into style. By coincidence, one of our board members, Janet Jordan, was surfing her way around and came across a group called the Association for Gravestone Studies. If you’re interested in gravestones, take a look at their page! But I noticed that the topic of one of their recent meetings was this very issue: will there be no gravestones to tell these stories in the future?

A great post - and one that should make us think about the future which will have no past.

ReplyDeleteI have always thought that it would be cool to have a really old gravestone when I die. I don't know exactly how that would work, but I'm sure there is some process that can be done to make a headstone look older than it really is. I would just get one engraved right now, but I have no idea when I am going to die. So it doesn't really work. http://www.sjcemeteries.com/memorial-products/

ReplyDelete