Tolomato Cemetery was open to the public as usual on the Third Saturday of the month, this year on April 19. But that week was also Holy Week, the week leading up to Easter during which the events in the life and death of Christ are remembered, and I was in Madrid, Spain, watching the processions that reenact or commemorate some of these events. And as always, I thought of St Augustine and wondered what we did back in the days when we were a Spanish colony and had the customs and practices of any Spanish colony. Spanish customs are very formal. Here we see a procession of Royal Halberdiers, who guard the Royal Palace, accompanying a Good Friday Procession.

The 16th and 17th centuries are considered the Golden Age of Spanish sculpture, and many of the figures carried on the processional platforms (called “pasos”) date to this period. They are very beautiful figures, carved of wood that was then finished with gesso (a fine layer of a plaster-like substance to give a smooth finish) and carefully painted. Some processional figures are known as “figuras de vestir,” meaning they were meant for dressing. In those cases, only the hands, feet and heads were carved, and the rest of the body was basically a wooden and wire armature that could be dressed in lavish robes and then posed on the paso. But many of them were full carvings, such as this beautiful “Cristo Yacente,” Christ Lying Prone, which was brought out on Holy Saturday in Madrid. This is a mid-20th century figure from Olot, a town north of Barcelona famed for its religious statuary.

Did we have these in St Augustine? We certainly had our version of them, probably not as sumptuous, but we know from an inventory done in Cuba at the end of the First Spanish Period, when all the church goods were brought from St Augustine to Havana before the arrival of the British in Florida, that we had numerous statues and small pasos, meant to be carried by 2-4 people. The one you see above is being carried on the shoulders of about 14 people; in the photo, it’s actually resting on posts while they wait to move on to the next street. Big processional floats such as the one below can weigh from one to three tons, and are carried by 30-40 people, but there is no indication that St Augustine ever had anything this large.

However, mentioned in the Havana inventory is a figure with moveable arms and an “urna de cristal.” Often a crucifix would have a figure of Christ where the arms were attached with leather straps so that the figure could be taken down for Good Friday and the arms moved to lie at the sides. The figure was then often displayed in a glass casket, or “urna de cristal.” Details are a little lacking in the inventory, so we don’t know the size of the figure, but in the colonies, I have observed that they are often about 3/4 size. Mexico produced a lot of beautiful and elegant religious statuary so ours may have come from Mexico; on the other hand, we were under the bishops of Cuba, and the Cubans generally seem to have ordered their religious goods from Spain.

At that time, at the end of the First Spanish Period, the parish church was Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, Our Lady of Solitude or Loneliness, which is an image of the Virgin Mary after the death of Christ. We certainly would have had a figure representing her, although probably not as magnificent as the 18th century figure you see below, being carried through the streets of Madrid by some 30 people, accompanied by penitentes (hooded penitents), drummers and a large band.

During the Second Spanish Period, when Tolomato Cemetery was active, about a third of the town’s religious goods were sent back to St Augustine from Havana. Another 3000 pesos worth were ordered by the Bishop of Havana from Barcelona, but the ship was captured by pirates just as it was arriving and taken to Charleston. It’s unclear whether the Spanish were able to ransom the goods back or get them back in some other way, and whether any of the goods made it to St Augustine. In any case, anything from that period would have been destroyed in the 1887 fire that destroyed the interior of the Cathedral.

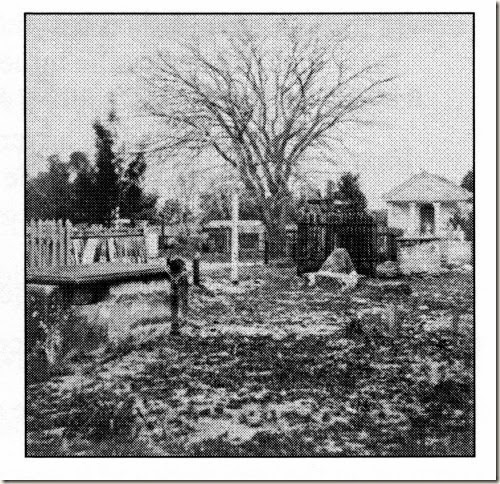

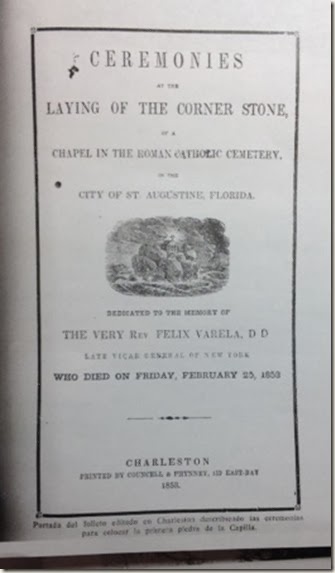

And the Varela Chapel at Tolomato, built in 1853, was always simple. As seen in the above 19th century photo, it is described by the Cubans who arranged for its building as having a carved mahogany altar – the elaborately carved parts of the current altar are from that original altar – an ebony cross with silver tips, mahogany candlesticks, a carpet on the floor and a painting of the Transfiguration behind the altar. Everything except the aforementioned carved parts of the altar has disappeared over the years. But we know that in 1801, when General Jorge (Georges) Biassou was buried, he had clergy in vestments, soldiers marching, and horses with plumes bearing him to Tolomato Cemetery…so perhaps we can assume that St Augustine once upon a time had its modest version of what we see below in the streets of Madrid.