Spending Christmas in Santa Fe, New Mexico, I came across an unexpected

trace of St Augustine, or more properly, of Florida.

As we all know, the Franciscans established an extensive mission chain in

Florida, starting in the 16th century. It lasted until the 18th century, when

it was finally destroyed by British and hostile Indian attacks.

La Natividad de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe

de (or possibly

"del")

Tolomato was one of these missions, having started in Georgia in the 16th

century, relocating to Florida in the 17th century and finally moving to the

site that is now Tolomato Cemetery in the early 18th century. At one point, Tolomato probably looked like this New Mexico cemetery below, although minus the plastic flowers.

Franciscan administrative areas are divided into provinces, and

"our" Franciscans were from the

Provincia

de Santa Helena de la Florida, which had a

convento in Havana that served as its convent, seminary and

headquarters. They founded a

convento

in St Augustine, at the site where the St Francis Barracks are now located, on

land given them for this purpose in 1588. The wooden

convento and its library, alas, were destroyed in 1702 by the

English pirate Robert Searles, but it was rebuilt in stone sometime in the

mid-18th century, only to be turned over to the British shortly thereafter when

Britain received St Augustine in the settlement of the French and Indian War in

1763. This more or less terminated the Franciscan presence in St

Augustine.

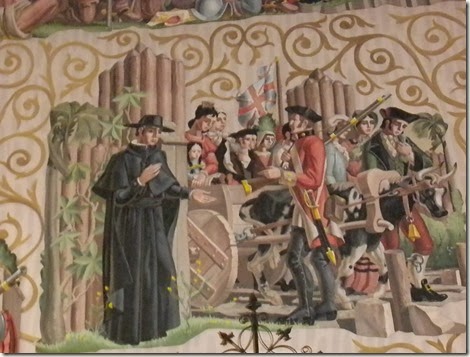

However, I found one of our Franciscan community a long way from home, in the

Southwest where he died in 1781 during an Indian revolt. I found this out from

a rather unexpected source, a painting done in the late 18

th century

(with very little information offered about it, unfortunately) on display at

the New Mexico Museum of History in Santa Fe.

It shows two friars, wearing the grey-blue

habits worn by these missionary Franciscans, standing in front of a scene

depicting their deaths. They were both clubbed to death at their remote mission.

While the sign next to the painting attributes the scene to the Pueblo

Revolt, this turned out not to be the case. The well-known Pueblo Revolt in

what is now New Mexico, the culmination of Indian conflicts with the Spanish administrators

over the years, began in 1681 and was over a few years later; in fact, only 12

years later, the Spanish returned, since the idyllic era that the revolt’s

leader, Popé, had promised never materialized and conditions were in fact worse

than before for the Indians (who were also now vulnerable to hostile tribes

such as the Apaches).

But in the

meantime, several hundred Spanish settlers and 21 friars had been killed.

But reading the text, I found that the Franciscans in this painting were

killed nearly 100 years after the Pueblo Revolt, and in fact, the places

mentioned were not even in New Mexico.

Who were they and when and where did they die?

Reading the information under their portraits, we find that the friar on

the left was Fr. Francisco Garcés, who took the habit in his native Aragon, Spain,

and went directly to the Franciscan missionary school (

Colegio Apostólico de San Fernando, but more about that some other

time) in Mexico City in 1763.

He died at

the “

Misión de la Purissima Concepcion

del Rio Colorado” in the area rather vaguely known as Sonora (a formerly

disputed territory now part of Mexico, Texas, Arizona and even California) in

1781 at the age of 42.

The other friar was Fr. Juan Antonio Barreneche, a native of Navarra, Spain,

who had come to the New World, specifically, to Havana, where he was took the

habit and was ordained, becoming a member of the Franciscan province of

Santa Helena de la Florida. This,

of course, was during the period in which St Augustine was no longer Spanish,

so the Franciscans no longer had a presence in our town.

After ordination, he went to the missionary school

in Mexico City, and from there, accompanied Fr. Garcés to the mission, where he

arrived in 1779 and died a holy death there in 1781 at the age of 31. It is

recorded that during the attack, he continued to hear confessions and give last

rites to the Indians and the Spaniards until he himself was finally killed, one of the many who died in what looks to us like a barren and unpromising land.

Having eliminated the possibility that they died in the Pueblo Revolt, I

moved on to other possibilities.

There were

several different tribes in this area, the Yaqui, the Pima, the “Moquis” or

Hopi, the Quechua, etc. and at various times, particularly as conflicts flared between

peninsular Spain and the

criollos of Mexico

and then between Mexico and the North American settlers in the West, there had been

many fierce but generally brief conflicts.

And of course, there were several missions dedicated to the

Purísima Concepción (Immaculate

Conception), for whom the Spanish and particularly Spanish Franciscans had a

great devotion. Below we see

La Conquistadora, a Spanish statue that is now an image of the Immaculate Conception, brought to Mexico by Franciscans in 1625 and eventually arriving in Santa Fe, where it has been a devotional focal point for centuries, through all wars and disturbances and crises.

One mission of that name turned out to have been founded by the Jesuits,

which disqualified it immediately; another important mission of that name was

founded by the Franciscans, but it was in San Antonio, Texas. And then,

finally, thanks to the miracle of the Internet, I found that a

Misión de la Purísima Concepción had

been established in 1779 in what is actually now a part of California, a place

now known as Fort Yuma (right across the Colorado River from the city of Yuma,

Arizona) by

Padres Francisco Tomás Hermenogildo

Garcés and Juan Antonio Barreneche.

It didn’t last long, because there was an uprising

of the Quechan (or Yuma) Indians in 1781, and while it was directed at the Spanish

administrators, the missionaries were killed as well, even though the mission

population tried to protect them. The

mission itself was destroyed and in its place a fort was built by the US

government some years later in the 19th century. And then in 1919, it became a mission again,

and is now known as St Thomas Indian Mission, which constitutes the easternmost

parish of the Diocese of San Diego.

There is a monument to Fr. Garcés at the mission. Below is a photo, from the town’s website,

but better photos and a more detailed history can be found at US Mission Trail,

a site maintained by a devotee of the missions.

So while the museum’s caption on the painting was completely wrong, it’s a

story that certainly was repeated throughout the Franciscan missions and no

doubt reflects the situation in New Mexico as well.

The text underneath the painting tells the personal side of the friars’ stories.

Let’s translate that of Brother Juan Antonio,

who passed through Cuba at the same time that most of St. Augustine’s former

residents had been long established around Havana.

Here is his story:

V. R. del Ven P. Fr. Juan Antonio Barreneche, Originario del Pueblo de

Lecazor en el Reino de Navarra, tomo el Santo habito en la Prov. De Sta. Helena

de la Florida, en el Convento de la Avana, hizo tránsito y se afilió en este Apostólico

Colegio el año de 75, en el de 79 fue destinado a las Missiones de Sonora, Estando

de Ministro en la de la Purissima Concepcion del Rio Colorado, y en compañía

del Venerable P. Fr. Fran. Garcés, se sublevaron los Yndios y el día 12 de

julio de 1781 le quitaron la vida a palos. Se advirtieron in este V. Religioso

mientras el motín algunas cosas prodigiosas y después de quatro meses de enterrado

su cadáver se hallo casi incorrupto Fue Religioso mui apacible, humilde, pobre,

penitente y Oediente, con cuias virtudes y otras en q[ue] se exercitó constante

dio exemplares pruebas de su Apostolico espíritu. Pasó de esta vida a la eterna

de edad de 31 años.

[Religious Life] of the Saintly Fr. Juan Antonio Barreneche, a native of the

town of Lecazor in the Kingdom of Navarra, who took the Holy habit in the

Province of Santa Helena of Florida, in the Convent of Havana, was transferred

and affiliated with this Apostolic College in the year [17]75, and in [17]79, was

sent to the Missions of Sonora, having his Ministry at the mission of the Purissima

Concepcion del Rio Colorado [Mission of the Immaculate Conception on the

Colorado River], accompanying the Saintly Fr. Francisco Garcés, when the

Indians revolted and on July 12, 1781, they took his life by clubbing him. During the riot, some remarkable things were

observed about this Holy Religious and four months after his burial, his body

was found to be almost incorrupt. He was a very gentle friar, humble, poor,

penitent and obedient, who through these virtues and others that he constantly

practiced gave an example that was proof of his Apostolic spirit. He passed

from this life to eternal life at 31 years of age.

So we find a connection between Spain, St. Augustine, New Mexico, Mexico, Arizona, California, numerous Indian tribes, and, most important of all, St. Francis. Below we see the Nativity Scene in the Cathedral Basilica of Santa Fe, since, after all, the Nativity Scene as such was introduced by St. Francis in 1223 and it also continues to this day.